A Personal Reflection on the Peace and Justice Pilgrimage

by Dr. Nick Quinton, Director of Discipleship and Adult Ministries

In the early morning hours of November 11, 2022, just over twenty of us gathered at St. Paul’s United Methodist Church for a trek to Montgomery, Alabama. We were set to visit the work of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) on the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, and the Legacy Museum. All of us who took the trip are from different stages of life, including an 11-year-old, those who have grandkids that age, and plenty of people in between. Our organizers had advertised it with both Saint Paul’s and Trinity UMC as a Peace and Justice Pilgrimage. The stated aim was simply to deepen our faith in Christ and stoke our desire to love one another. Given our distinct backgrounds, there was no guessing what the trip might mean to each of us. Today I give thanks for the goodness in God’s grace that brought us together and our shared commitment to embark on a life-changing trip.

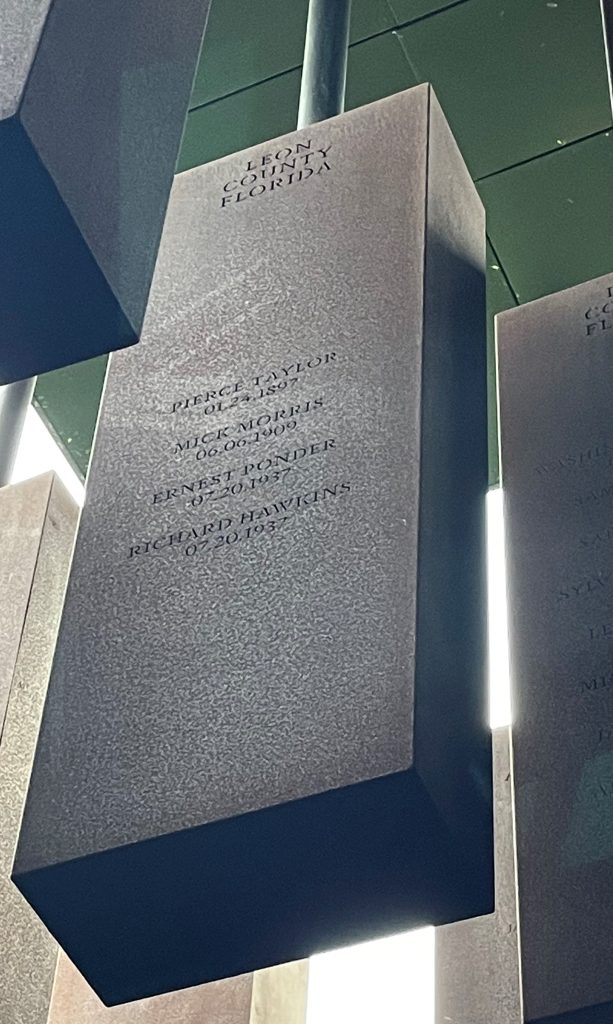

I had some notion of what we would encounter as we prepared for the journey. This is a trip I made in spring 2021 with my father, sister, and a group of folks from across the Southeast. All of us in that group had shared the work of anti-racism for over a year before we embarked. I thought I was prepared. But shortly after I entered the Legacy Museum, the jarring reminder of the brutality endemic to trade in enslaved people brought forth emotions that suggested I was not prepared. My disquiet deepened as we moved through newspaper clippings and public declarations, illuminating how the promise of Reconstruction was foiled and the realities of the Jim Crow South grew directly out of the trade in human beings. The line of evidence the Museum curators presented drew me forward into how the system of mass incarceration we have today is the latest link in this brutal chain of exclusion and oppression. It is a chain built with violence that has threatened Black lives since the very first ship landed in the Virginia Colony with enslaved people aboard. I roiled with what I felt as we left the Museum to visit the Memorial for Peace and Justice. I found no quiet there either. The Memorial brought out so many of the same feelings. On approach it was unsettling as I reckoned with the enormity of the installation and experienced the significance of the metal columns on display that were hanging: one column for every county, or parish where a lynching has been confirmed. The lives of all those humans, black-bodied with the same sacred worth given to all of us, taken in a massive campaign of terror lynchings, became very real as I read their names etched on the columns. It was an intense experience—one that has deeply impacted my dad, my sister, Katie, and me. What I didn’t know was how all of this would sit with this new group of disciples.

Our invitation for this trip was to pilgrimage. Far different from tourism, we went to be transformed through engagement rather than consume what there was to see. To quote Trevor Hudson in A Mile in My Shoes, “we [went] as pilgrims, not as tourists; as learners, not as teachers, as receivers, not as givers; as listeners, not as talkers” (2005, p. 18). In hindsight, it may be better to say we, ourselves, were consumed by all we encountered. There is much to learn. There is much to receive. And there is much to hear.

I can’t speak for everyone else on our pilgrimage, but transformation has come for me. EJI has collected many stories to take in, and the result is emotions stirred deep. I was particularly shaken by how commonplace so much of this violence was in the life of people I know, including my own family. My dad’s side of the family is from Obion County, Tennessee. As our ancestors headed west out of North Carolina, they couldn’t get across the Mississippi River, so they backtracked east 30 miles or so and settled in and around what is today Troy, Tennessee. Grandpa was born there in 1933, the youngest of twelve. They never had much, just a poor farming family. They were salt-of-the-earth folks, working the land and making ends meet as best they could. But it wasn’t all a simple bucolic life. Grandpa grew up in a place hardened to racial violence. The last recorded lynching in Obion County was of a man named George Smith in 1931. Grandpa wasn’t born when Mr. Smith was murdered. But his siblings, all older, were alive, and I have a hard time believing the oldest of them weren’t aware of the killing, as well as his mother and father. I don’t know what they thought or felt about the lynching of Mr. Smith because this is a part of growing up in rural West Tennessee he never discussed. He told me plenty of stories about his childhood, yet this went unremarked. I can only guess as to why he didn’t mention it, though I do know racial violence was never directed at him or our family. Whatever my family members did or failed to do in Obion County, lynching was not a threat because of the color of our skin. This is a revelation to me not because it is true, but because it went unremarked for so long.

EJI’s work is jarring if you are open to what they present. This pilgrimage now serves as a reminder of how close I am to white racial violence and the necessity to make sure it doesn’t go unremarked for my family. In Montgomery, I heard a part of Grandpa’s story, our story, that we don’t tell. He grew up in the midst of a lot of people who at best tolerated gruesome racial lynchings and at worst endorsed them. It’s not just rural West Tennessee. At the Memorial and the Legacy Museum, it is clear how widespread this violence has been and is. It’s a lot to take in and brings up a lot to wrestle with. I want to be careful here. Deep feelings of embarrassment, shame, and guilt, even anguish, welled up inside me. I learned the “other” side of these stories. I was raised with them as a child of the rural South. Stories of celebration and grievance passed down about my ancestors and their contemporaries to enshrine their chivalry and moral character, a recounting of what life was and is like for me and mine. And it is a whitewashed account. Being white has shaded so much of how I understand the world. On our pilgrimage, I encountered the voices of others who shed light on the shaded parts of familiar stories. These voices stirred my empathy with what feels like an invitation into Christ’s ministry of liberation.

It is in God’s grace that I wrestle with how to respond to all of this. The thought that keeps coming up for me is what it means to interrupt the lines of racial violence that weave through the stories I grew up with. When I see what has happened, and happens still, to people with Black skin by people who look like me, I can’t help but feel guilt, shame, and more. But I can’t stay there. And thanks to God’s grace I don’t. A friend once told me that I carry a lot of white guilt. Maybe I do. That isn’t the point of this story nor our trip. Far from being mired in self-loathing or anguish, I found hope. Not some naive hope that things will magically change. I found hope in kin- and friend-ship. I am deeply grateful for the work of Rev. Becky Rokatowski, Amy Leach, and our very special guest Priscilla Hawkins in setting up an incredible experience. I am also thankful for everyone who went on this pilgrimage. As we shared stories, worship, and communion together before we set out to come home, all the feelings of the emotion wheel washed over me. But in the final tally, it was hope that reigned. Hope in the empathy and resolve each person on our pilgrimage found to labor for a just society. Hope in our common calling to God’s work. And hope that things can get better. After all, who are we if not Disciples of Jesus Christ laboring for the transformation of the world? And so it goes for the people who set out on our Peace and Justice Pilgrimage, and so many others. Praise be to God.